| Spring calving is already starting in some parts of the U.S. and other areas aren’t far behind, which means now is the time to prepare for their arrival. Calf scours is probably the most concerning issue for any cow-calf operator. Half the battle against scours is understanding why it develops and what factors play a part in the infection of young calves.

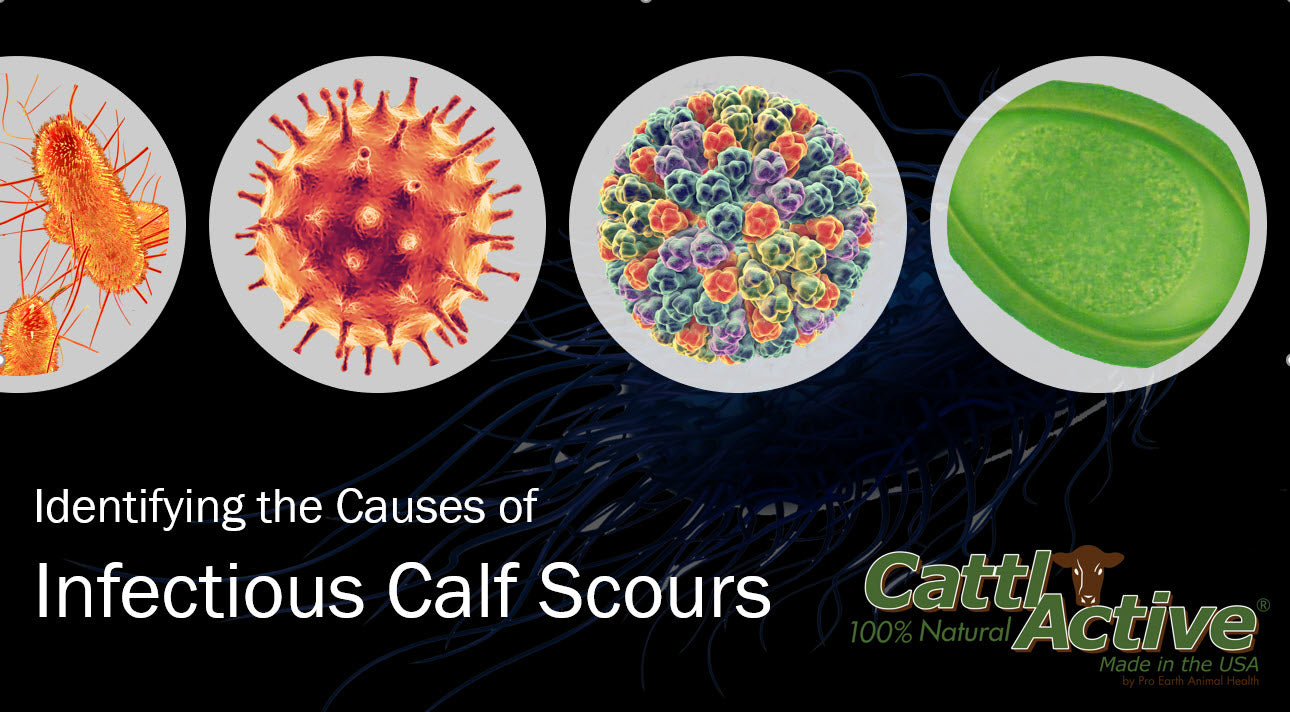

The most common cause of calf scours is infection from a viral, bacterial or protozoal contagion. The most prominent of these pathogens are outlined below. |

Many bovine viruses can cause diarrhea as a secondary symptom; however, there are two main viruses that target the GI system itself. Viral infections tend to have the easiest time replicating in a host that has a weak immune system and a delicate GI system.

RotavirusesThere are several strains of rotaviruses that can infect neonatal calves. Because of this, it is the most common infectious cause for scours in calves from 4 days to 2 weeks old, but it’s not uncommon to see calves both younger and older contract rotavirus. Poor hygienic conditions are one of the biggest factors in the spread of rotavirus to calves. Asymptomatic adult cattle can shed the virus through their feces, leaving calves with low immunity at high risk for contracting the disease. Unfortunately, it can also be spread from exposure to pig and rabbit feces, making it all the more important to ensure a sanitary environment for calves. The rotaviruses target the intestinal epithelium (the cells that line the inner surfaces of the intestines), destroying the villi (tiny finger-like projections that help capture and guide nutrients through the gut wall). As this occurs, the calf is unable to properly assimilate the milk it takes in from its mother, allowing undigested and unabsorbed nutrients to pass through the gut. The end result is diarrhea that leaves the calf dehydrated and undernourished. It is estimated that the mortality rate for calves that contract rotavirus to be upwards of 50% when treatment is not initiated. CoronavirusesCoronaviruses are a common issue amongst livestock. In bovines, the coronavirus is spread by adult cattle shedding the virus through their feces and into the environment. Neonatal calves are then exposed to the virus, and because they still have immature immune systems, are highly susceptible to infection. Coronavirus, like rotavirus, will attack the epithelium (inner lining of the intestines), compromising the absorption of fluids and nutrients. Because of this, diarrhea ensues, leading to dehydration and electrolyte imbalances. Concurrent infections from both coronavirus and rotavirus can occur, and can also be present with or shortly followed by a bacterial and/or parasitic infection, as well. Other Viral InfectionsThere are a few other viral infections that can lead to scours, but are less commonly found in the majority of scours cases. Nonetheless, it’s important to be on the lookout for any signs of these diseases in the herd. Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus (BVDV)Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus can infect neonatal calves on occasion. It causes diarrhea and oral lesions and ulcers, leading to subsequent acidosis and scours. Unfortunately, this is a severely debilitating virus and is often fatal to calves that contract it. Infectious Bovine Rhinotracheitis Virus (IBR)Infectious Bovine Rhinotracheitis Virus is associated with some cases of calf scours. Although it is not of gastrointestinal origin, it manifests as ulcers and erosions in the esophagus, causing difficulty eating, thus causing the calf to experience the symptoms of acidosis and scours and in many cases is fatal. |

Bacterial infections are a quite common cause of calf scours. Because bacteria can live in an environment for an extended period, preventing exposure may be a difficult task in a contaminated environment. Poor sanitation practices are one of the leading causes of bacterial exposure and consequent disease; most are spread via shedding of the bacterium through feces of carrier animals. Other sources can include contaminated water or feed, but these are less likely to spread disease in young calves.

E. coliE. coli is a gram-negative bacterium commonly found in the intestinal tract of most animals. It can, however, become pathogenic; some strains cause severe illness, including intestinal infection or septicemia (blood infection). These different strains are known as either being enterotoxigenic, meaning the effects are seen in the gastrointestinal system, or septicemic, which indicates the pathogen has entered the blood stream and traveled to various parts of the body, including organs and joints. In calves, enterotoxigenic E. coli is the most common and devastating form, making it the most prominent cause of bacterial diarrhea in calves, typically 3-5 days of age. E. coli is most commonly contracted through ingestion of the bacteria, which is shed through the feces of carrier or infected cows and calves. E. coli is particularly difficult to isolate, as carriers can show no signs of disease at all, but regularly infect other neonatal and adult cattle. Some of the most common places for calves and cows to ingest E. coli are from unsanitary living conditions such as contaminated bedding or feed troughs and water sources, diarrhea-stricken calves in calving pens and the skin on the udder or perineum of the cow. Enterotoxigenic E. coli adheres to the walls of the small intestine. As it multiplies it gives off toxins that prompt the calf’s body to send fluids into the intestines, causing potentially fatal diarrhea in the first three days of the calf’s life. Further along, there is the possibility that a calf will develop enterohemorrhagic E. coli, in which a shiga-like toxin is released. This toxin, with a behavior much like the action of rotaviruses and coronaviruses, destroys the intestinal villi and causes bloody diarrhea in older calves, typically between the ages of 2 – 5 weeks old. Regardless of the age of the calf, due to the severity of diarrhea associated with E. coli and the hemorrhagic nature of the disease, calves often develop severe scours due to the dehydration and potential anemia that can occur. While it is also possible for the calf to contract E. coli via inhalation, causing other disease processes, for the sake of this application the focus is on the enterotoxigenic form. Salmonella sp.Salmonella is the second most common cause of bacterially-mediated scours in calves. Because it can create its own toxin that is released when the bacterial cells are damaged, it can be more difficult to treat without causing more damage. Salmonella most commonly occurs in calves that are six days old or older, making colostrum antibodies almost completely ineffective against it. Salmonella can be spread quite easily and rapidly via saliva or feces of cattle and other animals, or through water supplies. It can even potentially be spread via contact with a human carrier, making hygiene of handlers, the environment and equipment essential to prevent its spread. Since Salmonella can cause severe diarrhea, it can lead to scours with all the associated symptoms, including dehydration, depression and emaciation. Clostridium perfringensUnlike many other bacterial diseases that take time to reach their peak, C. perfringens can come on suddenly. This tenacious bacterium creates and releases toxins that can cause acute illness in calves of almost any age. Poor calf management practices can be blamed for many cases of C. perfringens. Lengthy separation of a calf from the mother is perhaps the biggest contributor to calf scours caused by C. perfringens infections. While it is often present in the environment and to a lesser extent in adult cattle, in the right conditions the rapid growth of this bacteria is what allows it to become a problem. It is most commonly found in calves that may go for extended periods of time without nursing, causing them to consume an excess amount of milk once reunited with the cow. This excess can create an environment in which C. perfringens easily reproduces, growing quickly and releasing toxins that will overwhelm the calf’s system. In some cases, calves die without any obvious signs of disease or distress. Clostridium bacteria of all types can be found in soil, poorly-stored feed such as silage, milk or colostrum that has been improperly stored, water sources and unsanitary calf pens. Given the poor rate of recovery, it is more important to focus on prevention than cure in both beef and dairy settings. |

Because calves have not developed a strong immune system yet, they can be particularly susceptible to the ravages caused by protozoan infections. While a slightly less common cause of scours when compared to viral or bacterial pathogens, parasitic infections should still be considered a possibility when dealing with scours.

Cryptosporidium sp.As a protozoan parasite, Cryptosporidium can wreak havoc on the delicate intestinal walls of a calf, infecting them at the age of 1 – 3 weeks, then showing symptoms between 4 weeks and 4 months. Just as many of the other scours-causing pathogens will attach themselves to the cells lining the intestines, so too does this protozoan, damaging the microvilli that are vital to absorption of fluids and nutrients. The result is severe diarrhea that leads to the dehydration and electrolyte imbalances associated with calf scours. Once a calf is weaned, it will become asymptomatic, making it vital to try and prevent Cryptosporidium from infecting younger calves. Coccidia sp.Coccidia have a complex life cycle with rapid reproductive rates. This allows greater numbers to be shed via feces into the environment in a short amount of time. Because of the manner that it invades host cells within the intestines, reproduces and then bursts the cell walls, it can cause serious imbalances and irritation of the intestinal lining of calves, resulting in diarrhea (sometimes hemorrhagic) that can lead to the development of scours. Coccidiosis (the disease associated with infection by Coccidia) is directly related to how many oocysts are consumed. Thus, severe coccidial infections in both calves and adult cattle can be attributed to poor sanitation practices. |

| There are many steps that can be taken to minimize scours in your operation. As will be discussed more in-depth next week, solid vaccination programs, cows in good body condition at calving and careful management of calving environments can go a long way toward preventing the spread of pathogens that cause calf scours. |